A Meta Model of Change - to guide Change Leaders

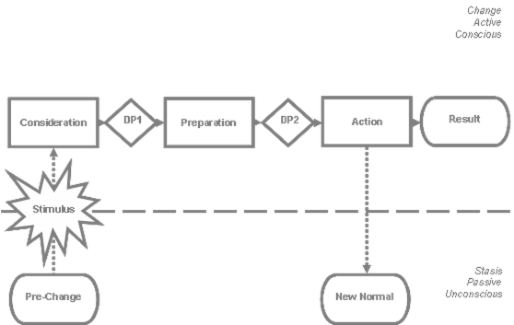

The aim of this model (Young, 2009) is to identify common themes from a broad range of change literature in order to better understand the basic principles of the change process and so improve Change Leadership. The benefit of considering both organisational- and individual-based change models is that each brings a different perspective to the stages of the common underlying change progression.

Pre-Change Paradigm. One of the strengths of counselling-based change models is that they identify ‘pre-change’ as the first stage of the journey. In so doing they draw attention to the seminal importance of understanding the pre-change paradigm. This is significant as, without a paradigm which encourages ‘active searching’, organisations, like individuals, often ignore early warning signs and wait until a crisis highlights the need for change. Many such organisational and personal crises could be avoided through regular, targeted stakeholder engagement. From the famed scenario planning of Shell to family discussions at the dinner table, the message is clear: make sure you know who is important to you, regularly canvass their opinion on what they want, how you are doing and what if anything could be improved.

Stimulus and Consideration. The counselling-based change models also highlight the importance of raising awareness to the signs of a potential need for change. Of course in today’s business and social environment of 24/7 news, e-mails, Blackberries, mobiles, Away Days, team and shareholder meetings, we are bombarded with external and internal stimuli – thankfully not all of which signify the need for change. But the mere action of considering the need for, or rationalising the reasons not to, change constitutes the next distinct stage of the journey. Active consideration from multiple perspectives, followed by an informed decision that the status quo is preferable, is a productive learning activity. What must be guarded against is the denial that any stimuli exist. However, it is also important to recognise that, even when change is required, the ‘disconfirming data’ is likely to induce anxiety which can prevent its acceptance as valid unless the threat is balanced with positive visions. So whilst the nature of the pre-change paradigm will determine the tendency to recognise or ignore the stimuli, in either case, the provision of Socratic questioning can assist in the achievement of the required insight and balance.

Validation of the Need. It is crucial to be really clear about who needs what, by when and why in order to establish whether a compelling need for change exists. Newton’s First Law of Motion applies: overcoming the inertia of the existing status quo will require energy and ‘only leadership can blast through the many sources of corporate inertia’. At this point the Transforming Leadership model is particularly appropriate as the transformational leader will take the initiative by articulating people’s new wants and needs in the changed environment, thus legitimising them and gathering support. The recognition of followers’ specific wants not only validates the social need for change but also secures support.

Preparation. The danger of a really energising need is that it may stimulate a premature reaction as opposed to an effective plan of action. Initiatives are regularly launched with no clearly established criteria for success and, by implication, no means of achieving them. Even more frequently organisations start to change things without first establishing a baseline without which it is impossible to monitor progress or to quantify the magnitude of change required or achieved. Beckhard and Harris (1977) provide a process to avoid such mistakes by assessing the present system and clarifying the desired future state; thus clearly identifying the scale of change required and allowing informed options to be developed to mange the transition. However, such preparation should not be done in isolation; early participation will uncover, at the very outset, the objections which are bound to emerge as resistance later. If these objections are faced when proposals are still in a fluid state, the solutions are easier to find, and the personal relations are less abrasive. Similarly early engagement of groups in the planning phase provides an advantage in that ‘if one uses individual procedures the force field which corresponds to the dependence of the individual on a valued standard acts as a resistance to change. If, however one succeeds in changing group standards, this same force field will tend to facilitate changing the individual’ (Lewin, 1947).

Commitment to Act. Many change models correctly acknowledge the significance of the decision that a compelling need for change exists (e.g.: Kotter, 1996). However, an equally important decision is confirming that the planned action is the most effective and efficient way to deliver the required change. The status quo may not merely be a level of equilibrium resulting from whatever forces the circumstances provide. Frequently the level itself acquires value. Strong commitment is needed to overcome this inner resistance to “break the habit” to “unfreeze” the custom.

Do-Check-Act. With a compelling need for change and an effective plan for its delivery, the change itself should flow by necessity – but this ‘transition stage’ must be kept aligned. Whether it’s a business improvement cycle of Plan-Do-Check-Act (Deming, 1982) or a personal review of your goals, current situation, options and actions the key message is that once the momentum for change has been successfully established, what is delivered must be actively steered. You either lead the change you want or end up managing what you get. However, within organisations such ‘steering’ must not take the form of micro-management. The leaders provide the vision and are the context setters. But the actual solutions about how best to meet the challenges of the moment, those thousands of strategic challenges encountered every day, have to be made by the people closest to the action – the people at the coal face.

Specific Results. If successful, the planned change initiative will deliver results which may range from millions of dollars of increased revenue in a multi-national, to improved health for an individual. In delivering such change the individual, or executive team, must learn from both success and failure. This ability to build learning and flexibility into the process of changing is a touchstone for ongoing success. But by the very nature of the fact that these are the results of a planned change programme they are, by consequence, dependent on the maintenance of that conscious change effort.

New Normal. By contrast enduring benefits will only accrue when some new behavioural ‘norm’ is embedded which continues to deliver the desired results as an unconscious by-product. When a month without a targeted improvement initiative or a day without exercise is unusual then business growth or personal fitness will be assured. Of course as soon as it is established the new normal becomes a pre-change paradigm for whatever emerges next. This realisation is crucial because in times of change it is vital to be in touch with the assumptions and theories that are guiding our practice and be able to shape and reshape them for different ends. Otherwise we run the risk of being trapped within existing mindsets – ‘practice is never theory free’.